Employee retention refers to the strategies an organization uses to retain its employees.

The fire service is steeped in tradition when it comes to our culture, workplaces and operations, and we have served our communities well. But our service (we are all in this together) has opportunities to improve and focusing on your most important resource, your people, is a great place to start. —Chief Cory Mainprize, Barrie Fire and Emergency Service

Employee retention refers to the strategies an organization uses to retain its employees.

Career firefighter job satisfaction is high while turnover rates are low due to job security, good health benefits and the prestige that comes with a job having a high level of public trust. According to the Insights Study, a majority of professional women firefighters love their jobs and would recommend firefighting to other women.

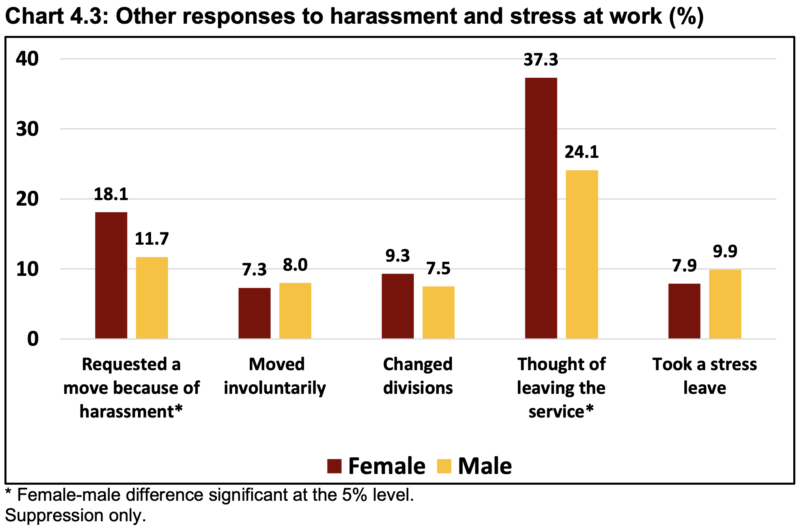

Although their job satisfaction rating is high, firefighters still consider leaving the service, with the Insights Study noting women significantly more so than men (over one-third of women, compared to one-quarter of men) due to harassment and stress at work.

From an employer perspective it is important to retain employees for many reasons, including the investment during the recruitment and hiring process. This section outlines issues plaguing fire organizations requiring the implementation of retention strategies.

Tokenism

Long-lasting changes in fire service culture cannot be achieved by simply inserting individuals belonging to underrepresented groups. Tokenism, the practice of making only a symbolic effort by hiring or offering small initiatives to only a small number of people from an underrepresented group to give the appearance of racial/sexual/gender equality within the workforce, is not an effective retention strategy. For instance, if tokenism is present, members from underrepresented groups may have a more difficult time gaining legitimacy and respect from their peers or even remaining on the job. Promoting diversity without also practicing inclusion can cause firefighters to leave the service.

Feeling of Value

Women may leave the fire service because they do not feel valued, face undocumented challenges (e.g., harassment, exclusion), or find it easier to quit rather than self-advocate. According to the US National Report Card on Women in Firefighting, higher levels of gender discrimination and sexual harassment are linked to lower overall job satisfaction and negatively impact emotional and physical health. However there is little data available on the exact reasons why women leave the fire service.

Equipment / Culture / Facilities

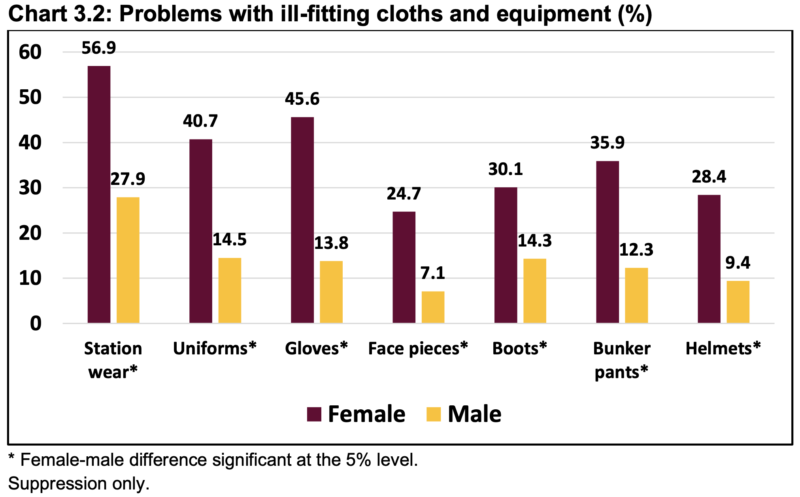

More than half of female respondents to the Insights survey reported problems with ill-fitting station wear, in comparison to a quarter of male respondents. Women also noted that “having to work in a workplace culture described as a ‘boys club’, having equipment that does not fit properly, living in halls that have not created space for women, being harassed and excluded all add up to a work environment where women do not feel welcome.” (page 42)

Inclusive facility design should make all facility users feel comfortable and safe. With more diverse crews spending longer shifts together, as well as government and fire service recognition of work-related stress and PTSI, the importance of thoughtful fire station design is growing. The physical workplace can be used to gauge the employer’s commitment to ensuring a positive work environment for all.

At best, inadequate facilities are an inconvenience to women firefighters. At worst, lack of proper station infrastructure can impact morale, job performance, and the ability of firefighters to follow health and safety regulations. Poor station facilities increase the potential for harassment and litigation. Facility shortcomings affect the ability of departments to be effective in diversity and inclusion goals from recruitment through to retention.

Good facility design will help fire departments recruit and retain:

Module 5.1 How to Conduct An Audit (below) details the steps involved to conduct an audit of your fire station to ensure its facilities are inclusive.

Equipping women with ill-fitting clothing and equipment reinforces the idea that they do not belong in the fire service. According to the Insights Study women face significant problems with ill-fitting clothing and equipment serious enough to make it difficult for some women to do their job effectively. These problems have a direct effect on their morale.

Access to proper fitting firefighting equipment, like SCBA and bunker gear, is a serious health and safety consideration. For example, small gloves designed for men do not fit most women’s hands often exacerbating the dangers of a hazardous work environment. As per Section 21 Guidelines of the Occupational Health and Safety Act, employers have a duty to ensure PPE is properly sized for worker safety.

Including women’s feedback in the clothing procurement process can prove to build an inclusive department, as well as including firefighters of various shapes and sizes when fit-testing new gear such as helmets and SCBA. Properly sized clothing and equipment should be provided at the beginning of the hiring process, avoiding firefighters being forced to petition for properly fitted gear.

The fire service can improve with following the Employment Standards Act and the Ontario Human Rights Code to address pregnant firefighter needs. Without coherent and lawful guidelines, firefighters are forced to make difficult and ill-informed decisions about their pregnancies and their access to maternity or parental leave. Pregnant firefighters should not be treated any differently from employees with other medical conditions who may require accommodations.

So we have nothing on paper that says what your accommodations are gonna be, what your hours of work are gonna be, what you have to do, what happens if you have to go to a doctor’s appointment, what happens if you have a miscarriage, because women on the fire service are three times more likely to miscarry. ... These are all great big things...worrying about what’s going to happen to you when you get pregnant or what the process is to let them know that you are pregnant and, you know, what you have to consider whether you still want to ride the trucks, none of this information is readily available. So that when you’re wanting to start a family, you’re spinning, cause you don’t know what’s gonna happen. That’s where women are really struggling, and the women are feeling like they’re not supported, and they have to navigate that process on their own. (Insights Study, page 71)

Instituting clear and defensible pregnancy and parental leave policies is essential to ensuring women feel included in the fire service. Implementing other progressive family life policies such as nursing, fertility treatment, fostering and adoption will benefit all employees, not just women, and will enhance workplace inclusion leading to employee retention. Review Module 5.2 How to Support Pregnant and Parenting Firefighters below.

Despite discrimination not being defined in the Code, courts interpret it to mean an intentional act of exclusion. There are different forms of discrimination, including direct, adverse impact, or constructive as well as systemic discrimination. Understanding discrimination including justifying discriminatory ruling is essential and should be a part of a firefighter’s training.

Harassment is defined in the Code (s. 10) as “engaging in a course of vexation comment or conduct that is known or ought reasonably to be known to be unwelcomed.” Workplace harassment is a serious matter and staff ought to be trained to ensure other members of the fire service understand its seriousness and create an inclusive environment.

Nearly 90% of firefighters in the Insights Study reported that their overall physical and mental health is good to excellent. However, when asked more detailed questions, a less optimistic picture emerged. Approximately 1 in 4 reported a physical or mental health issue in the past year. Female and male firefighters were equally likely to report most mental health conditions. Women reported more frequent work-related anxiety, panic attacks and lack of confidence.

For some women, the combination of dealing with the trauma of others while themselves being subject to harassment and discrimination at work led to significant stress related outcomes. In fact, almost half of all women surveyed felt emotionally unsafe at work. Anti-harassment and anti-discrimination training programs and policies are essential to improve mental health outcomes for all firefighters. It is important to note that male firefighters also experience harassment in the workplace, with one in four having experienced verbal harassment according to the Insights Study. Many departments already have the necessary policies in place, but supervisors may lack the skill to implement them appropriately. Departments with existing programs like peer support teams could increase employee access with more diverse teams. Departments may also implement women’s caucuses or other networking groups to create opportunities for employees to support one another.

As discussed in Section 1: Introduction to Change, your fire service should take the time to evaluate its policies around diversity & inclusion and appreciate if they do enough to retain current and continue to attract new employees to your fire service.

Undertake a SWOT Analysis to identify your fire service’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats relevant to existing policies. When considering external factors compare your policies and resources against those of the larger corporation (i.e., municipality). When considering your organization under present conditions and into the next 30-years, use the SWOT analysis to identify appropriate retention strategies that will help your employees feel they are working in an inclusive environment.

When undertaking the SWOT Analysis consider what is happening today, what is planned, and what needs to occur to ensure change is possible. With respect to strengths, be specific listing existing policies, procedures, equipment, training systems, budgetary constraints, anything that can help support the SWOT Analysis. Similarly, with respect to opportunities be sure to list desired improvements while including barriers that stand in the way. Use the analysis to help identify retention strategies that are aligned with your organization diversity & inclusion policies.

| Helpful to achieving objectives | Harmful to achieving objectives | |

|---|---|---|

| Internal Drivers | Diversity & Inclusion Policy | Not aligned with objectives / targets |

| Recruitment & Hiring Policy | Lack of resources / budget | |

| Healthy retrofit budget | Outdated policies | |

| Building under 10 years of age | Clothing and personal equipment ordered annually | |

| Health budget for new equipment | Lack of buy-in | |

| Fire hall’s policies recently reviewed | ||

| External Drivers | Corporate endorsement for retrofit of facilities | No corporate budget or endorsement for retrofits |

| Leverage training programs from other fire halls | Procurement policies outdated | |

| Leverage training programs from corporation | ||

| Procurement policies use varied suppliers – ability to access different sized equipment/materials |

Using the SWOT Analysis, begin to build your retention plan while aligned with your fire service’s vision, mission, and values in consideration of existing diversity & inclusion policies. To begin, identify your organization’s objectives using the Smart Goal method.

Example 1:

WHO – Golf Fire Service

WHAT – Review fire station design

WHERE / WHEN – Golf Halls #2, 12, 18 – December 31, 2021

STANDARD (MEASURABLE) – Review fire station design, assessing need for retrofits, ensuring facilities meet inclusive policy standards and providing list of recommended changes, including timeline and budget to implement changes

Objective 1: The Golf Fire Service will review Fire Halls 2, 12 & 18’s design to evaluate if retro-fit is necessary. The review will include recommendations including a budget and timeline. This will be completed by December 31, 2021.

Example 2:

WHO – Golf Fire Service

WHAT – Review / update parental leave policies

WHERE / WHEN – Golf Fire Service – June 30, 2021

STANDARD (MEASURABLE) – Review existing parental policies, including pregnancy polices ensuring compliance with current employment standards and human rights code and advise necessary changes and implementation strategy.

Objective 2: The Golf Fire Service will review all pregnancy and parental employee policies to ensure compliance with current employment standards and human rights code, making recommendations for changes and an implementation plan by June 30, 2021.

Based on your fire service’s retention goals begin to build your implementation plan. Recall this will include an outline of the program, budget details, responsibilities, and timing.

Using objective 1 from earlier, the steps involved with creating an implementation plan are listed in the table below.

Objective 1: The Golf Fire Service will review Fire Halls 2, 12 & 18’s design to evaluate if retrofit is necessary. The review will include recommendations including a budget and timeline. This will be completed by December 31, 2021

IMPLEMENTATION PLAN |

|

Review needs for retrofit of defined fire halls |

|

Programs: |

Create a comprehensive review and list of items/infrastructure (audit) requiring retrofit to create an inclusive fire hall |

Budget / Resources: |

People, time. (approx. cost) |

Procedures / Actions: |

Review existing facility for:

Review most recent building codes. Review Corporate Diversity & Inclusion Policies. Create a list of retrofit requirements. Create an implementation plan for a retrofit based on recommendations

|

Responsibility: |

Leadership: Review & approve recommended implementation plan. Building Inspections: Review recommended retrofit requirements and advise on building code and required building permits. Finance: Assist with creating retrofit budget. Management / Corporation: Approval of budget. Fire Chief: Approval of the Implementation Plan. |

Timing: |

6-9 months |

Your organization has identified different retention strategies and created an implementation plan, now it is time to assess its performance. Continuing with the previous example (Objective 1), the implementation performance can be assessed using a simplified scorecard method. Recall, when applying the scorecard, you are assessing your organization against a baseline – before implementing your plan.

| Objectives | Traffic Light | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Review Facility for Privacy with Safety, Lighting & Recreation | Comprehensive list of retrofit requirements created for each of the three halls. | |

| 2. Review building codes & policies | All building codes, policies investigated based on list of required retrofits | |

| 3. Create list of requirements, implementation strategy and budget | Detailed list of retrofit requirements for each hall developed; strategy plans complete, however budget still to be developed and approved |

| Core Values | Traffic Light | 1 | 2 | 3 | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| People | X | Retrofits, requirements and strategies in-line with Diversity & Inclusion policies | |||

| Culture | X | Retro-fit plans meet the needs of women in fire service however, improvement is still required with marginalized groups that their culture needs (e.g., inclusion of a prayer room) | |||

| Diversity | X | The retrofit strategy does not cover all the bases for women, and marginalized groups |

1 - Exceeds Expectations

2 - Meets Expectations

3 - Fails Expectations

Overall: 2

Overall, the retrofit plan as a retention strategy is a work in progress that details a comprehensive list of required changes. These changes still require review to ensure they successfully cover all marginalized groups, ensuring all employees' needs are met.

Thus far, we have walked through creating the retention strategies objectives & goals while building an implementation plan based on said goals. This plan should be aligned with your fire service’s diversity & inclusion policies. Next, we conducted a performance assessment against the implementation plan and based on the assessment we can create an improvement strategy.

Following through with retention Objective 1 and its implementation plan, create a plan adjustment:

| Objectives | Outcomes |

|---|---|

| 1. Review retrofit requirements | Identify retrofit items that do NOT currently support diverse cultural needs |

| 2. Create comprehensive budget plan | Work with Finance to create a comprehensive budget for the implementation of fire hall retrofits |

| 3. Review building permits and plans. | Work with municipal building department to create a comprehensive list detailing anticipated permits, costs and implementation strategy based on design timing and requirements. |

Retention and Recruitment for the Volunteer Fire Services: Challenges and Solutions U.S. Fire Administration (2007)

This project shares findings on what makes community members want to volunteer, how to retain volunteers, and the reasons why volunteers eventually choose to leave the organization. The document addresses challenges with recruiting women and other underrepresented groups, and reasons why female firefighters leave the job. Some of the language is dated, but the content is applicable beyond the American context.

Understanding the Volunteer Deficit Will Lead to Better Recruitment and Retention Public Safety, Kupietz (2019)

This article addresses how it is becoming increasingly difficult for fire departments to recruit and retain quality volunteers.

Meeting the Accommodation Needs of Employees on the Job Ontario Human Rights Commission (2008)

This section defines the principle of accommodation and how unions and employers can take an active role in their duty to accommodate.

Gender neutral or gender inclusive? What to consider in fire station design. FireRescue1, Linda Willing (2020)

This article is a great introduction however it doesn’t address the desire for privacy that trans and non-binary firefighters may have.

The case for space: Many firefighters want more privacy at the station FireRescue1, Linda Willing (2020)

This article speaks to how firefighters can still achieve camaraderie without communal space living situations.

Firehouse bedrooms and bathrooms: The ongoing debate. FireRescue1, Linda Willing (2018)

This article addresses some issues faced with open dorms and lack of bathrooms and the challenges faced finding the balance between health, privacy, and camaraderie in the firehouse.

Return to Work Plans for Ontario Workplaces Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act, Greg Thomson (2018)

This link provides useful information about return to work legislation, how it applies to employers, and the details that need to be included in a return to work plan.

A Guide for Managing Return to Work Canadian Human Rights Commission (2007)

This guide provides an outline of the key legal principles that apply to return-to-work situations, step-by-step procedures to guide your approach to case management, and a series of case studies demonstrating how you could deal with different hypothetical scenarios.

Emerging Health and Safety Issues Among Women in the Fire Service FEMA; US Fire Administration (2019)

This document speaks to occupational health and safety issues for female firefighters: recruitment and retention, heart health, mental health, inclusion, and cancer.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in First Responders and Other Designated Workers WSIB Ontario (2018)

This policy applies to decisions made on or after September 1, 2018, for accidents on or after January 1, 1998. The purpose of this policy is to outline the circumstances under which PTSD in first responders and other designated workers is presumed to be work-related.

Recovery and Return to Work First Responders First

This link specifically speaks to return to work considerations for a PTSD plan, and advice for accommodating a worker with PTSD. It also speaks to legislative requirements.

Employment Standards Act Queen’s Printer for Ontario (2020)

This link helps to understand one’s rights and obligations under the Employment Standards Act (ESA). The guide describes the rules about minimum wage, hours of work limits, termination of employment, public holidays, pregnancy and parental leave, severance pay, vacation and more.

Bargaining Equality Kit Canadian Union of Public Employees (2014)

This link provides many resources (for union members and those on a bargaining committee) on equality and measures to change the workplace to better suit workers, meeting the needs of members, and making workplaces reflect the communities we live in.

Bargaining and Equity Public Service Alliance of Canada (2015)

This link provides questions to ask when reviewing your bargaining demand(s) and/or employer proposals to see if there are any barriers for members belonging to one or more equity group.

Equity and Inclusion Lens – Handbook; A Resource for Community Agencies City for All Women Initiative (2015)

This City of Ottawa handbook is an interactive tool that will help you to learn about equity and inclusion and how to apply it in the workplace.

The Toronto Professional Firefighters’ Association’s Family Resource Guide TPFFA (2019)

This guide helps association members navigate pregnancy and/or parenting while working as a member of Local 3888. Other Locals or fire service leaders may wish to model items addressed in this manual since it is intended for anyone who is pregnant or parenting, adopting or fostering children, or considering any of these roles. While some sections of this document, especially those regarding physical job demands, are more focused on pregnant membership in the Operations Division, this document is intended as a resource to all members.

Most existing fire stations were built at a time when women, and non-binary and transgendered people were not firefighters. As a result, many fire stations lack adequate bathroom, changing, and shower facilities. Some departments have tried to remedy situations by simply placing locks on existing men’s washroom and locker room doors to help protect privacy. This stop-gap solution often intensifies people’s sense of exclusion and can limit access to necessary washroom facilities for all firefighters. It is imperative that fire departments invest in capital improvements.

Fire service leaders should complete facilities audits on all fire stations and involve employees in facility design. An audit should identify problems and limitations, areas easily retrofitted and others that require more substantive renovation. It should also help build a picture for future new facility projects. The way that facilities are used will evolve over time. Fire departments should commit to conducting a facilities audit on a regular basis to address new issues and to assist with future large-scale infrastructure planning.

Good facility design will:

The development of inclusive facilities requires commitment from all members of the fire department, from the rank and file through to leadership. Facilities assessments are part of regular health and safety planning and review and should not be siloed under the auspices of diversity and inclusion. Chief Mainprize from Barrie Fire and Emergency Services has his department incorporating “people-friendly design” that is gender inclusive without being gender focused.

Good fire station design includes:

When large-scale station renovations or new builds are not feasible, a clear, coherent policy on facility modification to accommodate firefighter needs is imperative.

In 2019, Toronto Fire Services completed a facilities survey of all its 82 fire stations. Survey questions included number of washrooms and designated signage, whether there were locks on doors, locks on stalls, and if change rooms exist outside of the dormitory space. Other questions addressed layout of shower facilities, placement of garbage receptacles in washrooms, and if there were appropriate areas for breastfeeding or pumping breast milk. A template of the Toronto Fire Services Facilities Assessment is available in the Appendix, as well as a working audit checklist template.

A template of the Toronto Fire Services Facilities Assessment is available in the Appendix.

1. What is the purpose of the assessment?

Determine the purpose of the assessment. Are you merely taking stock of what already exists or creating recommendations for change? Both actions are important. Goals may be to make stations more accessible, more inclusive, more private, more up-to-date, or more uniform. All of these outcomes should be considered as the assessment is developed so the right questions can be asked to get the answers necessary to achieve results.

Your assessment can:

2. What should the assessment checklist look like?

The assessment should include a mixture of objective and subjective questions. Objective questions seek information that is fact based, measurable and observable (How many washrooms? How many stalls in each washroom? Do stalls have locks?). Subjective questions seek information based on personal opinions, interpretations, and perspective (Where do firefighters feel comfortable changing? Do firefighters feel like they have enough privacy in the dormitory?).

Review the goals of your assessment to determine what should be included in the checklist. Note that minimum criteria listed in jurisdictional Occupational Health and Safety Acts is far below what most fire departments would consider minimum standards for fire stations.

Create common language.

Privacy and levels of comfort mean something different from one individual to the next. The evaluation process should begin with creating a common definition of some of the key phrases and ideas used in the assessment. This is to make sure the project team and participants are all on the same page and have a shared understanding of what is meant in the context of the assessment during each station evaluation. Language or terminology found in the assessments can be quantified by adding a rating scale. For example: On a scale of 1-5, how well does this station provide privacy for all staff?

What specific questions do you want answered?

The rule of thumb is: If two responses are needed, two separate questions are needed. Otherwise, extra time must be spent during data processing back-tracking to properly interpret the data. For example, instead of asking how many women/men/unisex washrooms are present and if there are locks, questions should be broken down to first determine how many women’s washrooms exist in each station then how many men’s, etc. The next question would be if there is a lock on the women’s washrooms, is there a lock on the men’s washroom, etc.

Include questions about the history of the facility being assessed. Such as:

Understanding the background of the station is valuable for the assessor and for the analysis. A station might get a positive rating at its current capacity, but with another apparatus added privacy may be affected. For example, the sleeping quarters and washrooms are fine for x number of firefighters, but if a second apparatus were added it would be uncomfortable due to lack of space for four or five extra people.

The assessment should include space for additional notes. The assessors will encounter unforeseen issues that should be documented. During the Toronto Fire Services facilities assessment, the team encountered a barrier to inclusion with computer access. In many of Toronto’s older fire stations, computers are kept in Captains’ offices which double as sleeping quarters. In part due to the paramilitary culture of firefighting, newer, younger, and female firefighters were uncomfortable requesting access to private offices in order to complete paperwork or online training.

3. Who should conduct the assessment?

The assessment should be done by a diverse team. Different assessors will have different answers to subjective questions, and a diverse team will enrich the data gathered. The assessment conducted by Toronto Fire Services used a small group of people who covered all stations. At each facility, the assessment should include firefighters who work at the station; they will have invaluable insight into how the facility is used. In the case of a unionized workforce, a union representative should be included in the audit team. They will have background information about issues in a station that may have been overlooked by others. For example, the union representative may know that women transfer out of a particular fire hall because of inadequate facilities, or the rep may have been part of a longstanding push to modify a station.

Policy on Preventing Discrimination Because of Gender Identity and Gender Discrimination Ontario Human Rights Commission (2020)

This link contains legislation explaining how accessibility to washrooms and change rooms must be granted based on lived gender identity and further states an organization’s washroom facilities and any related policy should not negatively affect trans people.

Designing for Inclusivity: Strategies for Universal Washrooms and Changerooms in Community and Recreation Facilities HCMA Architecture + Design (2018)

This document was created to help fill a gap in design knowledge around issues relating to universal washrooms and change rooms, and their provision in community and recreation facilities. It is a contribution to ongoing and evolving discussions around designing for inclusivity. It shares core considerations rather than comprehensive suggestions for all groups.

Creating a Breastfeeding Friendly Workplace. Ontario Public Health Association (2008)

This publication will assist your organization in creating a family-friendly workplace that will enable employees to achieve a balance between career and parenting responsibilities.

Fire departments across Canada struggle with implementing clear and legally defensible pregnancy policies for firefighters. Policy progress has been slow due to women’s limited inroads into the profession as well as gender normative stereotypes about women, pregnancy, and work. Firefighters and their employers are not exempt from robust employment and human rights law that ensures job protection and bodily autonomy for pregnant workers.

The gap between law and policy in the fire service has a significant effect on women’s emotional and physical wellbeing. Insights Study respondents had varied pregnancy and maternity leave experiences. Most stated that formal pregnancy policies were lacking and that they did not know who to trust to speak to or approach

concerning their pregnancy. They reported not knowing if or what type of modified duties existed or if their positions would be available upon their return to full duties.

So we have nothing on paper that says what your accommodations are gonna be, what your hours of work are gonna be, what you have to do, what happens if you have to go to a doctor’s appointment, what happens if you have a miscarriage, because women on the fire service are three times more likely to miscarry. ... These are all great big things...worrying about what’s going to happen to you when you get pregnant or what the process is to let them know that you are pregnant and, you know, what you have to consider whether you still want to ride the trucks, none of this information is readily available. So that when you’re wanting to start a family, you’re spinning, cause you don’t know what’s gonna happen. That’s where women are really struggling, and the women are feeling like they’re not supported, and they have to navigate that process on their own. (Insights Study, page 71).

Fire department administrators often unilaterally remove a pregnant firefighter from front-line duties thinking they are acting in the best interest of the expectant parent and the fetus. Some departments require firefighters to disclose their pregnancy as soon as the worker is aware of it. These practices are illegal.

What are the benefits of clear and legally sound pregnancy and family life policies?

Without clear and complete information, pregnant firefighters may be forced to make difficult decisions about their pregnancy and their parental leave. If departments are committed to building an inclusive workplace, they must ensure all members of the workforce feel valued. Under the law, pregnant firefighters should be treated no differently from firefighters with other medical conditions that may inhibit their ability to perform their job. This position is supported by the International Association of Firefighters (IAFF).

I did not tell anyone I was pregnant...because I didn’t know who I could trust. I didn’t know who I could trust in the union, didn’t know who to trust in the administration, to keep it private, didn’t know who I could trust. So that is definitely a problem I feel, as a woman in the fire department. (Insights Study, page 71).

When a firefighter is injured, whether temporarily or permanently, they may require accommodations. Similarly, pregnant firefighters may seek accommodations at a particular point during their pregnancy. Given the physical nature of firefighting, many fire departments have a modified or light duties policy in place to accommodate firefighters who become injured. National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) Standard 1582, Annex D provides guidelines on pregnancy accommodations, as well as some limited information about hazardous exposure risks during pregnancy.

The Ontario Human Rights Code’s principle of Duty to Accommodate is based on the right to equal treatment. Unions share with employers the responsibility to facilitate a worker’s accommodation needs. Fire administrators and unions should work collaboratively to form clear policy and collective agreement language for family life situations. When guidelines are unclear or policy language is illegal, employees cannot make informed decisions.

Best practices that support pregnant and parenting firefighters:

The Ontario Human Rights Code[3] protects pregnant workers from discrimination based on sex. It also protects those with caregiver responsibilities from discrimination based on family status. Firefighters in Ontario have used the protected ground of family status (see Oakville Award in Appendix) to successfully advocate for access to on-shift modified duties. Firefighters work unusually long shifts and arrange their child and family care needs around these shifts. Sometimes being accommodated on a straight-days schedule creates an undue burden on the firefighter.

Similarly, firefighters have had to advocate to remain on their shift cycle when promoted or transferred in order to accommodate child custody arrangements. It is to the benefit of both employers and employees if those family status needs are accounted for through clear policy language.

It has been the experience of some departments that the implementation of a modified duties program for pregnant firefighters has caused resentment in male firefighters who believe these programs confer special status on female firefighters. This tension is another way that women experience a sense of exclusion in the fire service. Departments can mitigate this tension in several ways:

Workplace accommodations are always specific to each individual’s needs; there is no gender-specific one-size-fits-all accommodation. Results from the Insights Study (p.55) demonstrate that women don’t want to be treated any differently from their male colleagues. Adherence to best practices in support of pregnant and parenting firefighters will help reduce the practice or perception of differential treatment.

Pregnancy and Family Resource Guide Template

In 2018, the Toronto Professional Firefighters’ Association (TPFFA) produced a comprehensive online Pregnancy and Family Resource Guide for its members. A copy of this guide is available in the Appendix. The guide was intended as a resource for questions about any pregnancy or family life situation. With over 3,000 members and an increasing number of women and younger hires, the TPFFA Executive Board was fielding an extraordinary number of questions about pregnancy and parental leave, childcare leave, and modified duties.

The TPFFA Pregnancy and Family Resource Guide has been presented through the IAFF to firefighters across North America as a diversity and inclusion best practice. The TPFFA has made this document available online for any department or association that wishes to model the format to create their own comprehensive resource.

The guide is a working document and is updated frequently as federal and provincial laws and the reality of family life evolve. A department should not wait until a first female firefighter is hired or a firefighter becomes pregnant before implementing relevant policy. The TPFFA guide is an example of a proactive document that anticipates future questions.

In response to the TPFFA guide, Toronto Fire Services (TFS) produced a new and progressive pregnancy policy and related guideline and FAQs. The TPFFA guide and TFS policy are the result of management and union working collaboratively on workplace diversity and inclusion and on responding to a changing workforce.

Lessons learned from Toronto:

The Toronto Professional Firefighters’ Association’s Family Resource Guide TPFFA (2019)

This guide helps association members navigate pregnancy and/or parenting while working as a member of Local 3888. Other Locals or fire service leaders may wish to model items addressed in this manual since it is intended for anyone who is pregnant or parenting, adopting or fostering children, or considering any of these roles. While some sections of this document, especially those regarding physical job demands, are more focused on pregnant membership in the Operations Division, this document is intended as a resource to all members.

Pregnancy and firefighting: Is firefighting bad for your baby? FireRescue1, Sara Jahnke (2020)

This article contains research impact of the job on pregnant firefighters, potential health risks to pregnancy, the impact on men, and the importance of exposure prevention.

Women’s Health in the Fire Service IAFF (2019)

This article speaks to women’s pregnancy experiences in the fire service, issues surrounding lack of policy, facilities for breastfeeding, and legislation.

Maternal and Child Health Among Female Firefighters in the U.S. Jahnke, Poston, Jitnarin, & Haddock (2018)

This research article analyzes the finding of 1821 female firefighters who participated in a self-report survey of questions about pregnancy including their departments’ policies and practices and their own experiences of pregnancy. Findings found important implications for policy and practice among women who become pregnant while actively serving in the fire service.

Pregnancy & Human Rights in the Workplace – A Guide for Employers Canadian Human Rights Commission

This policy will help employers, unions, and employees under federal jurisdiction to better understand their legal rights, obligations, and duties regarding pregnancy-related discrimination issues. It will also explain some of the employer benefits of providing respectful and inclusive workplaces for pregnant employees, identify potentially discriminatory practices, and offer practical solutions.

Pregnancy and Parental Leave Ministry of Labour, Training, and Skills Development (2020)

This link speaks to pregnancy and parental leave legislation in Ontario in accordance to the Employment Standards Act and the federal Employment Insurance Act.

Guidelines for Accommodating Pregnancy and Breastfeeding City of Toronto (2017)

The City’s Accommodation Policy outlines the obligation to accommodate individuals in accordance with the City’s Human Rights and Anti-Harassment/Discrimination Policy and Ontario’s Human Rights Code (Code). This guideline raises awareness and fulfills our shared obligation to accommodate employees, job applicants and service recipients based on the ground of sex, which includes Pregnancy and Breastfeeding. The Code requires that all employees, job applicants and service recipients receive equal treatment and opportunities regardless of their sex, including the right to equal treatment without discrimination because a person is, was, or may become pregnant.

NFPA 1582, Standard on Medical Requirements for Fire Fighters NFPA (2007)

Annex D of this standard is intended to serve as guidance for the re department physician in advising the pregnant firefighter of the risks associated with performing essential job functions and enabling her in decision-making.

See the following documents in the Appendix: